|

Although still 51 Squadron Commander, David set about the creation of the new 578 Squadron which officially came into being on 14 January 1944. Because of operational requirements and the fact that the near by Burn airfield was not ready to receive it, 578 Squadron flew initially from Snaith. Six days later, David set the fine example of leading it on a raid to Berlin and the next night to Magdeburg. On the night of 30 January he and eleven crews of the new 578 Squadron took off for the last time from Snaith in order, yet again, to bomb Berlin.

The move to Burn took place during the first week in February. Despite the very considerable amount of work entailed in organising the new Squadron, taking on new personnel, training them and attending to their welfare, these tasks and many others occasioned by his new command, did not keep him on the ground for long. On the night of 20 February 1944 he led ten aircraft to Stuttgart.

In the same manner in which David welcomed me into his Cub Pack eight years previously, so did he in respect of those, of whatever rank, who took up their duties at Burn. He went out of his way to treat aircrew and ground staff alike. Aircraftsman Dudley Brown remembers:

I was an A/C 2 flight mechanic when I joined 578 Squadron at Snaith and was one of the first to move over to Burn. We had all been drawn from different units, I was on ‘B’ flight, with Q-Queenie’s ground crew. Paddy Black, our Corporal, was an Irishman and we had been at Burn about three or four days and were chatting away on the dispersal when the Wing Commander’s car arrived. Paddy said ‘We’d better be a little careful - we don’t know what he’s like” so we lined up and, as Wing Commander Wilkerson got out of the car, Paddy called us to attention and saluted. The ‘Winco’ returned it and said “Ah! Corporal and what’s your name?”

“Black, Sir”.

“Oh” he said, “I suppose the boys call you Paddy”.

“Yes, Sir”.

“Well Paddy, I don’t want time wasted by saluting. You only salute me if the Group Captain is about. We’re here to do a job and I want you all to do your very best. If at any time you have a problem, come straight to me and I’ll do what I can.” Away he went with a “Cheerio lads” and that was that. We felt better for his visit.

Throughout his stay at Burn David kept a watchful eye on the welfare of those under his command and made it his business to know, or become aware of, virtually every man and woman on site and the diverse tasks they performed.

There can be no doubt that David’s popularity was derived from his prowess as a pilot, his ability to comprehend what was going on, to lead positively but in a manner understood by all and his great sense of humour. Flight Sergeant John Fleming the Australian rear gunner remembers:

I think ‘Wilkie’ was a hero to everyone who came into contact with him. Even after all this time I can recall several small events which portrayed a very human man with a great ability to make people feel at ease - this in addition to his obvious skill as a pilot and his undoubted bravery in the air and his high degree of management on the ground.

I had the honour to fly with him and on one particular occasion, after we had been airborne for some thirty minutes, his mike was turned on and over the intercom the rest of us heard a loud belch. Now we all knew that ‘Wilkie’ was an educated man and spoke in a cultured voice but this took us all completely by surprise. Some fifteen minutes later, his mike still switched on, we were treated to another belch and this activity was repeated several times, interspersed with instructions to various crew members. Somehow, after the shock of the initial ‘burp’ had worn off, it had a calming effect on me and I am sure the rest of the crew. Of course, nobody said anything to the C.O. - it was just accepted.

On another occasion, when we were all assembled for an operational briefing and after target details had been revealed, ‘Wilkie’ remarked that on the previous night’s operation, when we had been promised ‘no cloud over the target, we had, in fact, experienced 10/10 cover. He called on Flying Officer Casey, our Met Officer, to provide better news for the current operation. He fixed Casey with a deep scowl, which then broke into a laugh. Casey grinned and the rest of us joined in with the laughter. This relieved the tension of the Briefing Room although it did not detract from the seriousness of the events of the day.

David wilkerson at the controls of a Halifax Mk II bomber

Flight Sergeant John Wadia was the flight engineer in LK-L which landed back at Burn shortly after D-Day and was taxiing round to dispersal when, over the radio telephone a pilot was heard from another aircraft calling the Tower and querying “Who is that horrible clot coming in to land in the wrong direction on the runway?” David’s voice replied “You are you idiot - go round and try again.”

The remainder of March was taken up with the requirement to bring the Squadron up to strength but, in mid April, David led twenty-one aircraft on a night operation to bomb the railway yards at Ottignies. Two nights later he took a similar number to Düsseldorf and two nights after that to Karlsruhr where his own aircraft suffered damage which forced him to return on three engines. Two nights on he was out again to bomb the German town of Essen.

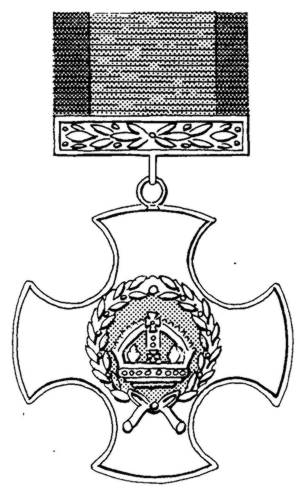

David’s work and achievements were officially recognised when, on 23 May 1944, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order. The citation in The London Gazette read:

This Officer has completed many sorties on his second ‘tour’ of operations. He has displayed high powers of leadership, great skill and determination, qualities which have earned him much success. He is a devoted and zealous Squadron Commander, whose great drive and tactical ability have contributed in a large measure to the high standard of operational efficiency of the Squadron.

The D.S.O

The next night, by way of celebration, perhaps, he led twenty-three aircraft to attack the important railway town of Aachen which was a major communications centre between Germany and France.

D-Day operations began on the night of 5/6 June 1944. Flight Sergeant C W Adams, rear gunner, remembers the briefing by Wing Commander Wilkerson for the raid that night to Mont Fleury.

He created a feeling of excitement among us. Although not being told specifically that this was support for the Invasion of Europe, we were as good as told, and knew from experience, what was to occur on this historic day. Like the rest of the Squadron’s aircrews he did not want to miss this trip.

On 22 June, twenty-four aircraft from the Squadron took part in a daylight attack on the huge concrete structures of the V-1 missile bunkers at Siracourt. Some heavy anti-aircraft gunfire was encountered on the enemy coast on the outward and return flights with a small amount in the target area. LK-J, flown by David, received damage to the wing flaps from ground gunfire but, despite this, it returned safely to Burn as did the rest of the Squadron. He was out again on the night of 12 July, taking part in an attack on the flying bomb supply dump at Thiveney.

Operational flying commitments aside It is unlikely that David ever received formal instruction in what today would be called ‘Industrial Relations’. He obviously understood the value of close co-operation at all levels and knew he could not expect interest, loyalty or even discipline, unless the morale of the people under his command was maintained. Airframe fitter Corporal Ted Bland, quotes an example how this was achieved.

I remember on one occasion at a welfare meeting I asked if it would be possible to permit some ground staff, due for weekend leave and who lived more than two hundred miles from Burn, to have a 'pass' covering them from Friday noon to 0800 on Monday because of the difficulty in making train connections.

After discussion, a consensus of opinion and a promise from me that aircraft servicing would not suffer, come what may, 'Wilkie' agreed saying, "I would like to have the prize being offered by the Bristol Aeroplane Company to the squadron with the best engine servicing record in 4 Group". I related this to all ground staff and they agreed to a man to try and win it just for him. Shortly after the war, the Bristol Aeroplane Company presented 578 Burn Association with a retrospective Commemorative Shield, beautifully hand carved in Walnut, in recognition of the high regard it had for the way in which we had maintained the Hercules engines fitted to 578 Squadron aircraft. This shield is now on display at the Burn Methodist Church .

It is sad that 'Wilkie' our revered Squadron Commander was not able to accept the honour personally, as we would have wished

Sergeant Colin Couper, bomb aimer, remembers:

‘Wilkie’ seemed to be revered by everyone, flying crews, ground crews, men and women. We always felt safe flying near him and we tended to overlook the fact that he wasn’t much older than ourselves.

On occasions when with us he was waiting at dispersal for the ‘off’ in the summer sunshine, he would wrestle with anyone who would provide the opposition. I’ll never forget when he had need to take an aircraft on a test flight, more often than not the man occupying the rear turret was not the regular gunner but Padre Hollis, obviously in his element as a substitute.

David undoubtedly would have been fully aware of strict regulations concerning unauthorised occupancy of aircraft and misuse of Air Ministry property but there is evidence that he chose to turn a blind eye on such things, especially if he considered the well being of those in his charge to be under threat. Pilot Officer Ron King, navigator, gives an example:

Returning in the early hours of the morning from an operation, tension among the crews would sometimes run high and when we at last reached our billet and got settled into the warmth of our beds, the question arose as to who should turn out the light. Nobody relished the thought of padding barefooted across the rough floor, therefore it was not unknown for one or other of us to use our recently issued revolver and take pot-shots at the bulb until darkness was achieved. Apparently, this procedure was followed by other squadrons as it became so commonplace that Group issued an order that all crew billets were to be inspected by a senior officer and any evidence reported. On one occasion when Wing Commander Wilkerson was making his regular rounds, he walked the length of our billet and, glancing up at all the holes in the ceiling, remarked that our hut appeared to have attracted more flak damage than any other on the airfield - and left it at that!

Stories of this kind abound and many more can be found in the book Based at Burn MkII, but David was also quite capable of exerting discipline when the need arose. For example, there were the incidents described by Flying Officer Bert Morris, the Canadian navigator:

Wing Commander Wilkerson, in my opinion, was the finest officer that I had the privilege of serving under during my four-year stint, as a Canadian in the RAF. That in itself is a tribute because some of the Canadian and British officers did not always see eye to eye. He was always fair, but could also be firm when the situation required. I was one of the escorts when a rear gunner was brought up on a charge because he had neglected to take his parachute on operations, which caused the pilot to abort the mission. After hearing all the evidence and accepting the gunner’s statement of total responsibility, the Wing Commander reduced the gunner to the ranks and set the pilot’s promotion back a few months for failing to check his crew properly.

On another occasion our crew was detailed to pick up an aircraft at Snaith and fly it to Burn. Since this would only take a few minutes by air we did not take any parachutes. We had no sooner parked the aircraft at Burn when we saw the ‘Winco’s car approaching and, on arrival, he asked us where our parachutes were. When we explained he proceeded to give us Hell (in a nice way of course) and posed the question “What would you have done if the airfield had been under attack or you had been attacked yourself during the flight?” He was right of course and we could understand his logic. ‘Wilkie’ had spotted us from the control tower. He seemed to have eyes in the back of his head and missed nothing.

One afternoon all aircrew on the station were summoned to the briefing room. ‘Wilkie’ took the floor and explained that certain incidents such as low flying over a girl friend’s house, shooting up other airfields, coming in to land 180 degrees off, and many other stupid stunts, would have to stop. He did not mention any names but everyone knew to whom he was referring. There must have been at least one hundred and fifty aircrew present and you could hear a pin drop. He commanded utter respect from us all.

A well known Halifax photgraph of David Wilkerson, with his Flight Engineer and Wireless Operator below

David’s final operation with 578 Squadron occurred in the early morning of 30 July 1944 to Battle Area ’G’ near the Normandy village of Villiers Bocage, an area comprising woodland and small fields. The hedgerows, many of which were centuries old, were so thick in places to resist even bulldozers. Clearly with narrow roads between the stout and tall hedgerows, this was just the terrain in which tanks could so easily be ambushed. It was here that the 7th Armoured Division fought a bloody and inconclusive battle with the German Panzer Lehr Division. Because of low cloud making target identification difficult, and with the close proximity of Allied troops, the Master Bomber ordered the mission to be abandoned. David, who had used his initiative and flown beneath the cloud level, was heard talking to the Master Bomber, offering to carry on with the mission as he could clearly see the aiming point, but this action was forbidden.

It was entirely correct of David to accede to the instructions of the Master Bomber, even if he happened to disagree with them at the time. Although in many ways he was a free spirit and liked to act individually, his RAF career could not have reached the very successful stage it did unless he was prepared to submit himself to discipline.

Having completed two ‘tours’ of operations, borne the responsibility of creating a Heavy Bomber Squadron and probably, as a further career move, David was posted on 28 August 1944 to 9 Course Empire Central Flying School, Hullavington, Wiltshire. Before leaving Burn he was, willingly subjected to the exuberant antics of his fellows of all ranks. Flight Lieutenant Ken Davies recalls:

When it was announced that ‘Wilkie’ was to leave the Squadron, some members of the Mess, feeling an urge to demonstrate their appreciation, decided to chair him about a bit on their shoulders. The carriers passed through the width of the double doors from the bar easily enough and at great pace but poor ‘Wilkie’, sitting up there, couldn’t fit in with the height, with the result that he had a sticking plaster on his head for several days.

Flight mechanic Fred Charles recounts:

I well remember his last operation from Burn. He led fourteen of the Squadron aircraft on the daylight raid to Villiers Bocage in support of the Allied army. We all awaited his return and were heartily relieved when we heard his radio call prior to starting the return circuit and everybody went outside to watch him land. His Standard 10 motor car had in the meantime been hoisted on to the roof of the Fire Station building by his fellow officers. Balloons were attached all round it and streamers festooned the bumper bars. He laughed like a drain at the sight of it!

A few days later he left the Squadron. His car was taken down from the roof, ropes were attached to either side of it and he was duly and symbolically towed away by officers and men toward his new unit