|

Elsie Mackinson (formerly LACW Hope 2135436 WAAF)

July 14th 1942 was my twentieth birthday. At that period of the war all single girls reaching the age of twenty had to register for national service. I received papers calling me into the army but as I preferred the air force I volunteered and just one week before Christmas in 1942 I found myself on my way to Gloucester where I had been instructed to report.

The train was absolutely packed and there was standing room only. Coming from the country I had never seen anything like that before. The time came when I felt ready for my sandwiches which were in my suitcase but where was the key? It was round my neck on a piece of ribbon where my Mum had recommended that I put it for safety. How would I get the case open? I could hardly move my arms as there were people all around. Hunger struck. Here goes; out comes the key. With my head bent down I had at last found the key. I reached the case. Success! But what an embarrassment when all the other young people around me burst out laughing! This was my number one lesson learnt on my way to the outside world.

On arrival at Gloucester camp we were all taken into a room and given a thorough medical check. Fancy treating us like that - we hadn't even been given a cup of tea. Everything was hurried because of Christmas so half the intake was rushed through to receive their uniform and the other half had to wait until Boxing Day. Christmas Day was ‘free’ but we were not allowed to leave camp. I can clearly remember all lining up outside the cookhouse singing all the modern songs of the day. "You are my sunshine" was sung out into the cold, frosty air. We had a long wait. I was still in civilian clothes.

There was no rush for me to get into uniform as I wasn't that keen to become a WAAF. My thoughts were back home with the loved ones that I had left behind. Here, though, I was ACW 2135436 Hope.

We had three weeks drill at Compton Bassett in Wiltshire (where we had moved to). There was much drilling and plenty of pep talks. The introduction to the gas chamber was the worst. It made your eyes turn red for ages. I remember all the RAF regiment coming away on our arrival with tears rolling down their faces. Poor fellows, what an embarrassment!

We were told that six of us were being posted to Brandesburton on the east coast. Our journey took us through London. I had never been nor seen the underground railway. Someone said that we had to hurry as the doors would close. In flew cases and kit bags and they were all in a pile in the doorway. We had to climb over the top of them. "All in?". "Yes". Away we went. Lesson number two learnt. Always leave room to get in through the door yourself!

Arriving in the camp very late in the evening we were taken to the mens' cookhouse for a meal. Was this really the life that we had expected? A kind airman came to us for a chat and told us not to walk on the campsite as it was a very long way. We were to insist on transport. The duty W/O appeared and told us where to go. Taking the advice of the airman I asked how far it was. My answer to his reply was "that's impossible". The time was 11.30 p.m. and we had been on the go since five that morning. Getting through the London underground one little WAAF with us couldn't even carry her kit bag. We just sat. It didn't take them long to provide transport. We were very pleased. The journey took us over a quarter of an hour all piled in a lorry. How could we have walked?

We had arrived at last, but where? The duty corporal took us to the nissen hut. "Here you are then." We looked and looked. A tin hut among a dozen more in the middle of a field. It was a brilliant moonlit night and freezing very hard. Where were the ablutions? "Sorry, not working. You must wait until you are back in the camp in the morning." Where was the heating? "Sorry there isn't any. Here are your beds, three blankets, the mattress biscuits and ‘roly poly" pillows’. She had gone as had warmth and hoped for sleep.

After being signed in on camp the next day we realised what a very long way we would have to walk so we felt very grateful to the kind airman. Having been allocated our duties I was told to report to a W/O the following day. Imagine my horror when I came face to face with the W/O for whom I had flatly refused to move and whose orders I had not obeyed on the night of our arrival. He greeted me with "Not you again!"

While staying on that camp I became a trainee Wireless Operator and finally returned to Compton Bassett for a six month's wireless course.

My close friend for the next six months, Maud, was a girl with whom I had arrived on the course. She proved to be a good companion and we had a very happy time. We were among the 34 unit on this training camp. Maud was very good at cartoon drawing and many times passed me one while we were busy doing our homework at night. We had been for our tea in the cookhouse and our allocation of butter was put on a piece of bread. Maud had seen an extra large piece of butter so she reached over to get it only to be shouted at by the airwoman in charge "Airwomen take the first slice!" I still have the cartoon that she drew. Another cartoon arrived on my bed one evening. We had been instructed to do drill on the parade ground in one of our free periods. The Sgt in charge of us had forgotten how to do it but anyway we had to go. I must say that she was doing her best but compared to the RAF regiment over on the other side of the parade ground we were not quite up to standard. The station Warrant Officer had seen us. Alas he instructed the Drill Sergeant to come over and "show us how" and how he did! Being a Drill Sgt he was just waiting for such an opportunity. Up, down, about turn, left wheel, halt, quick march, about turn, about turn! We just couldn't keep up. Some were a little behind with the instructions and the group split in the middle with one half going one way and the other half the other. By this time three girls had fainted with exhaustion. However that was the last time that we were sent on drill. It was more good cartoon material for Maud.

We were only allowed out of camp at the weekend. In order to get a late pass, until midnight, you had to have an ‘excellent’ for the inspection of your hut. This was very hard to achieve. I well remember that as a last effort to help the girls I filled an empty 71b jam tin with wild flowers which I had picked off camp. It was bluebell time and with dark pink and white campions I made an air force symbol with red, white and blue circles. I well remember the girls coming running at lunch time to tell me that we had got a late pass. It proved to be an extra job for me for the rest of my stay. It got more and more difficult to find the flowers. By July we had formed our little groups of friends and on the day of my 21st birthday I was told not to go to the cookhouse for my tea. Maud, with the other girls, eight of us in all, went across to the NAAFI. The girls had arranged and paid for a tea party. A Scots girl had saved the cake that her mother had sent her. It was fruit cake and very special. They had made a frill from writing paper and the candles were safety matches. By some miracle they were all lit and blown out without it catching fire. A white tablecloth was on the table and that was a treat in itself. We all had a very happy time. I was called on to make a speech and the happy evening ended, or so I thought. I had just got into my bed when they all pounced on me. I was no light-weight but they dragged me into the middle of the room and I was ‘bumped’ twenty one times. A solid ending to a memorable time. My cards were mostly home-made by the girls along with the ones from my family.

We finally came to the end of our course. We ‘Sparks’, as they were called indicated our trade. Where do we all go now? We were told that wireless operators had now been made redundant owing to interception by the Germans. Tele-printing was taking our place. We could go to do interception but that was not my choice. We were told to write down where we would Hke to go. This surprised us very much. Could we really choose where we wanted to go? I took the risk and put the nearest aerodrome to my home. Imagine my surprise when I was told that I was being posted there to work in Signals. It was sad to leave all my friends. We were all split up and I never saw Maud again but we kept in touch. I still have her cartoons reminding me of our happy times.

Would a six month's wireless course equip me for all the various jobs put before me? Well I had to wait to find out. What follows tells of my adventures.

Based at Burn

After quite a few months at Snaith in Yorkshire, working along with girls on tele-printers and telegrams, I was posted to RAF Burn, a satellite station to Snaith, only three and a half miles from home. I had hit the jackpot and here my very happy eighteen months of the war were spent.

The twenty months I spent at Burn aerodrome were the happiest time I had during my three and a half years in the air force. I was known as LACW Hope 2135436, my name was Elsie, but I was always referred to as 'Faith'. After training as a wireless operator at Compton Bassett, we were immediately made redundant, tele-printers had come into use. We were allowed to choose where we would like to be posted. I'd put 'Snaith' which was near my home so imagine my surprise when I realised I had been sent there.

After a short while I was sent on to Burn, where my happy memories began. I was told to report to the signals maintenance section and my surprise when I got there was that they had never had a WAAF before. Sergeant Davies in charge was not pleased and I can't say I was thrilled either! The airmen at break time greeted me and after a while I was accepted. I was given various jobs, among them was checking the crew's helmets before ops. One officer refused to trust me until after two nights when a rear gunners ear phones hadn't worked they passed them over to me to repair. It needed soldering iron to a wire and I got all the jobs after then. All had settled down when one morning the W.O. walked in, they had forgotten I was there! I was told to report to the signals officer Flt.Lieut. Leigh. I was put to work in the signals office where I was needed most, so my jobs were very varied and scary.

It was at this time in late autumn 1943 that I had to report to Sgt Davies at Wireless Maintenance Section. Whatever work was I going to be able to do there? Well I soon found out! Sgt. Davies was a small fair-haired married man with pleasant manners. He very soon announced that he was having "no nonsense" in his section. They had never had a WAAF in maintenance before and he certainly was not pleased at my arrival. He was even less pleased when, at break time, about eight of his men arrived and cheered at the sight of the new recruit. It was very embarrassing and how does one set about convincing a Sergeant and his men that I too was not pleased with where I had been sent? I quietly went about the tasks that I was given and I was quickly accepted into the daily routine.

After showing the skills of being able to use a soldering iron I was soon handed the job of checking air crew helmets before the airmen went on operations. I must add that the aircraft were Halifax Bombers so a lot of my time was taken up with this task. Again I met up with opposition for being a WAAF. One wireless operator refused to let me check his aircrew's helmets and said “No, I will do them myself”. After returning twice from operations with the air gunner's helmet and communication not working he said "Oh well, I guess you had better do them." After checking I soon realised that an earth wire was broken off. This had only affected the helmet when on ops and had not shown up on his tests. I got out my soldering iron. We had been trained on our course to use one. He called out "What are you doing?" Why, soldering the wire of course. Meanwhile he gazed on in amazement. I duly handed over the helmets. Next morning he returned to apologise for his lack of confidence in a WAAF. The helmet had worked and I had gained a little more respect in my daily tasks. I kept the workshop a little tidier and was asked to do office work and book-keeping in the Sgt's Office.

At last I was accepted, enjoying my work and the company but knowing my place amongst this all male section. It was a very cold winter and the airmen returned frozen in the morning from working out on the cold airfield. We had no means of making a hot drink. I learnt that a bucket of cocoa was put out in the cookhouse every morning at ten o'clock. I obtained a round biscuit tin from home and one of the men put a handle on it. I could now set off on my bike for a tin of cocoa. How welcome it was to see the tin sitting on the big iron stove. Mugs were produced and the hot chocolate was enjoyed.

(Elsie is fourth from the right)

(Elsie is fourth from the right)

We had all got into our daily tasks, the WAAF had been accepted and we were all happy to continue like this. Alas, it was not to be. One morning the Warrant Officer of the Signals Section walked in and saw the tin of cocoa. The little WAAF had been completely forgotten. I had done a little too much for the men's comfort. I was needed in the Signals Section Office so next day I had to report to Flight Officer Leigh. It was sad leaving. We had learnt to respect each other and even Sgt. Davies was sorry to se me go. No doubt the men missed their hot chocolate on cold mornings as well. Someone else would now have to undertake maintenance of helmets and even the Sergeant would have a little more office work to do.

Rather timidly I presented myself the next morning at the Signals Office. Next door in the same building were housed the Intelligence Section. It was written in bold letters on the door and looked rather frightening. What ever went on behind those doors? However, today I had to experience the workings of the Signals Section and here I was.

After introducing myself I was taken across to another building which housed the tele-printers and telephonists. My job was to receive all telegrams sent in and out of camp. This was the only means of contact with families at home. Telegrams were often sent. I also had the task of keeping up to date with the amendments of all the call sign books. I was back working amongst WAAFs and my new experiences had begun. After a while I found everyone very helpful and we were all settled in our new routine. I occasionally saw my friends back at Maintenance. Spring had arrived so the hot chocolate was not missed quite so much.

I found it was quite easy to ride home in my off duty time as bicycles were issued if you could ride one. After making enquiries I found that I could get a living out pass and I was very pleased when one was granted. I was back home living with my parents and cycling into camp for 8.30a.m.. I went home at5 p.m. so it was just like a normal job. Burn camp was a really happy one – it all stemmed from the example set by Wing Commander Wilkerson.

Going into camp one morning I passed an old black Austin Seven upside down in the ditch. I stopped to look and was pleased to find that it was empty. How could they have escaped, I wondered? Back at work I was told it belonged to a Canadian pilot and his crew. They had been returning back to camp, seven of them, from one of their usual ‘ops’ at the Londesborough Arms Hotel at Selby. Luckily nobody was hurt. I discovered that it was not the first time this had happened and it certainly wasn't the last!

My work became more interesting and challenging as the weeks progressed. One morning I was asked to go along and help the telephonist as one girl was ill. Have you ever seen one of those old switch boards with little numbers flapping at you all the time? I sat down on my chair and found that it was on a swivel. How I wished it would screw me down to the floor. By now I was used to receiving and sending messages on the phone. This was something that was not very familiar with girls of our age as hardly anyone had a phone before the war but now here I was at the connecting stage. I was first told that I was not to keep No.1 and No.2 waiting. "Why?", I asked. It was because they were the Group Captain of the Station and the Wing Commander. Oh dear! I didn't feel I wanted to be interviewed by them. Of course the regular telephonist took that board and I operated board number two.

All went well as the morning progressed and with her help the boards were kept clear. But what happens when she needs to run off for five minutes? Oh dear! I was again instructed to answer No.1 and No.2 immediately, to leave the others and do the best I could. That's it and here I am in charge of the two switch boards - not much to bother about you may think but when you are sitting on the swivel chair it is another matter. Here goes! All is going well. I've got that one through and yet another. Then No.1 came up and my heart took a leap. Thank heavens it was an inside call and I hadn't to go through to Group Headquarters. I put it through and took a deep breath but then they started and I just couldn't keep up. Flap, flap, flap. "Hold the line;" good; I've got that one through. "Just a minute, trying to connect you." I was pleased when it was an inside call and I was able to stop some of those little round things flapping at me. The door opened and Joan was back. Her trained skill soon had everything under control. Eventually lunchtime came and I was off duty. It had been a long morning.

Sports Day arrived. Yes, we had a Sports Day with a dance in the evening. The sports started at 2 p.m in the farmer's field. Those not on duty had to attend. Cycling at least seven to eight miles a day I felt in good trim. Here I knew a little about what I was undertaking. My first race was on and we were called to the line. We're off! In the lead. This is great! I arrived comfortably at the tape held by two officers from Intelligence Section. I tripped and over as I got to the tape. A voice said "Dear me, she has crash-landed!" I had indeed, just where a cow had been. I looked up and to my horror there I was ‘smelling so sweet’ but not of the scent that I would have preferred to have used for Intelligence. I had good support from the Signals Section and felt a little embarrassed to have to walk up and receive five prizes. I well remember cycling home for tea a little weak at the knees. After refreshment I set off back on my bike the four miles to the dance. At the end of the day I was thankful for a bed on camp back with the girls. Again the call came to go and relieve the Signals Clerk. My typing was only at the tap, tap, tap stage which Mac the Signals Clerk had trained me to do. Here I am again. What now?

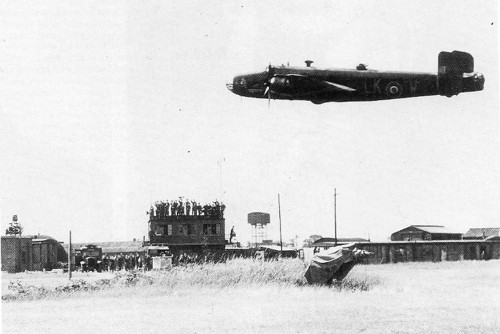

One morning at work a great noise was going on at the next building to us. A crane was hoisting a little black Austin seven onto the top of the flat roof next to flying control. It belonged to members of the crew of LK-W, who, piloted by Canadian Flt. Lieut. Max Baer were going on their last flight to complete their tour. There was great excitement. The car was decorated all over with white strips of toilet paper, (all the planes flying over Germany were painted with white strips) and the words ‘it's on the house’ were painted on the building. It was not unusual to see this little car in ‘the ditch’, as all the crew piled in on a night out at the Londsborough Hotel in Selby.

Three met balloons were floating up above the car, just asking for trouble. Imagine my surprise when I was called to do a log for the R/T operator. Everybody very excited. Group Captain Warburton, Wing Commander Wilkinson, aircrews not on ops and airmen all gathered up on top of flying control's roof to watch the ‘shoot up’, which was the done thing on the last run. The call came through, he was back, he was given the runway to land, we watched through the windows in front of us.

Then it all happened! The Group Captain and Wing Commander flung themselves to the floor shouting "get down". The pilot had seen his car and was heading for flying control intent on bursting the balloons. The R/T op. got under the bench we were writing on, I was just rooted to my chair, the noise was deafening and as LK-W went over head, I saw a wheel pass the window, he was on course to burst the balloons, which he did! Up jumped the Wing Commander, grabbed the R/T, and transmitted an instruction to land using language I never recorded - I hadn't even heard of some of it! The plane was brought into land immediately, we heard that F/O Baer had been up in front of the Group Captain and Wing Commander. The car was removed, all was quiet with nobody hurt.

My first job each day was to go to Flying Control and collect the secret call sign for the day and to return and type it on rice paper for the aircrew to carry with them on ‘ops’. I had to have this correct. It seemed so important as lives were at risk. I got through the rest of her leave with only the everyday happenings. It was then back to work on my telegrams and amendments. Another day I had a call from Flying Control. The RT operators needed a 'logger’. This involved writing down what was said over the intercom. I was getting used to being called for this relief job.

The tension grew in Control as LK-H drew near to the time of the aircrafts' return. Would they all return safely after their raid? They were counted and checked on landing. Yes they were all back safely, thank goodness. One day I was called and the planes were not on operations. One aircraft was out practising ‘circuits and bumps’. They said it's quite easy - all you have to do when the aircraft calls in is to give the height to fly in the circuit and say "Prepare to land, runway 26". Away the RT operator disappeared to the dentist. Again I was left with a strange job. My heart went bump, bump, throb, throb. The pilot was speaking to me and I must answer. "Prepare to land. Runway 26." Gosh, yes! There it was, the large Halifax Bomber landing in front of my very eyes. It had worked. I got quite excited to see it take off again and land. At last the operator was back on his job and I was free to return to my little desk.

Sundays was the day I cycled home for lunch. We still did manage the small joint and Yorkshire pudding. Mum's cooking was well worth the effort of another seven miles on a bike. It was a hot day and I had been to the church parade in the lovely little church on camp. The service had been well attended which said something for the good Padre we had.

When the service was over I set off home with my thoughts miles away with my brother who was fighting in North Africa with the Eighth Army. Mother had been through it all before in the First World War with my father away. She was thankful that I had chosen to be near her for company. What a hot ride it was so off came my jacket and hat. The tie was next to be dropped in my basket in front of my bike and then up went my sleeves. I felt much cooler now. Away I sailed along the long, straight road. I was well away from camp and I thought nobody would see me. Suddenly I was overtaken by a small RAF van which pulled into the side. Had I been caught ‘improperly dressed’? Out stepped the Padre and to my relief offered me a lift. He put my bike in the back and never mentioned how I was dressed. Saved again!

Around this time, as I rode in the mornings, I often met an Italian prisoner of war cycling to work on a farm. At first I felt a little nervous as it was a long straight road with nobody in sight. I wondered how he would react to me in uniform. I need not have feared as we passed at about the same place each morning. He said "Good morning", to which I replied and then we each went on our way.

One morning, a week or two later, when I was back at my desk, news came through that Canadian pilot, Flt.Lt. Baer, the owner of the old black upturned Austin 7, his tour of ops over, was going to be presented with the DFC on camp. I think Wing Commander Wilkerson had forgiven his ‘shooting up’ the Control Tower. Preparations were made. It was a cold spell and great coats had to be worn. As our WAAF officer did not have a great coat, the notice went up that WAAF’s were not to wear coats. The morning arrived and we were all on parade with our coats on as it was so cold. Our officer arrived with no coat so she made us take ours off. We were marched on parade on the airfield with our teeth chattering while all the men wore big coats for the ceremony. Time to move off now and we were very pleased as it was so cold out on that open air field. We were taken down a side road to be dismissed. The WAAF officer turned left but forgot to give us a signal so on we marched. The RAF regiment behind us burst into howls of laughter. Our officer turned round to see us down the road. The girls leading our section had done it to get their own back because of how we had been treated on such a cold morning with no coats. A short time after she was moved from our camp. It had been noticed that we were without coats when orders to wear them had been given from the Group Captain.

Christmas came round and I was on duty for Christmas Day. Mac, the Signals Clerk and I tried to make the best of Christmas morning by filling stockings with small amounts of things we could produce. We had great fun watching the Signals Officer looking to see what Father Christmas had brought. We were given a traditional Christmas dinner but work had to carry on as usual.

Fun and Tragedy

Then winter came and we woke up to heavy snows. All aircraft were grounded. Before lunch the Signals Officer came in and told the telephonists to monitor all calls from the armoury. Word had got out that the men in the Armoury and Transport Sections were going to attack Signals and Intelligence Sections after lunch with snowballs. We found out, through the telephone calls, that they planned to leave the armoury at the other side of the airfield with lorry loads of snowballs. All hands on deck! The Signals and Intelligence men found places to hide outside our offices and they too had stacks of snowballs piled up. WAAF were not allowed to take part so Mac and I had a good view through the window. At two o'clock we could see the lorries approaching across the airfield. What a shock they got when they arrived! Never had we seen such a snow fight and I guess we never will again. Mac and I had to quickly lock our doors and keep away from the windows as snowballs flew in all directions. They were trying to take the building but they never got in so I guess we won. The fight was over and we went back to our duties with a light-hearted cheer. I am sure we all remember the day.

The night raid to Bottrop of 20 July 1944 was a dreadful one for 578 Squadron which suffered the loss six aircraft and forty-two valuable aircrew members. I remember the following day very well as one of my jobs was to send out and receive telegrams on the station. I sent thirty two telegrams to the next of kin and received many back in the afternoon, something I will never forget. Two of our returning aircraft only a few miles from Burn crashed in mid air over Balkholme near Goole. All fourteen aircrew were killed.. Sad duties such as this, but not on this scale thankfully, became a regular occurrence. I am very pleased to learn that a splendid memorial now stands at Balkholme, in a garden set mid way between the two crash sites.

I recall that shortly afterward, Wing Commander DSS Wilkerson DFC was awarded the D.S.O and we attended a big parade on the airfield to mark the occasion. But it was not long before we all assembled again to bid him farewell, for he had been moved to another station.’ He was obviously very sad to leave the Squadron he had created and unable to finish his speech. He was a very fine commander, a real gentleman and an inspiration to us all and we were very sorry to see him go. A few hours later while I was on duty I received a telegram from Grantham station in which he thanked everyone on 578 Squadron for the wonderful send off and saying he was sorry he hadn't been able to finish his speech as he had been overcome by the occasion.

Only a few weeks had passed when we received word that ‘Wilkie’ had been killed whilst taking a short flight as passenger in a Baltimore aircraft. His request had been that in the event of his death he should be put to rest in Selby cemetery so as to be near his 578 Squadron boys. Accordingly, his funeral service was held in our little church on camp, in the presence of high ranking officers from 4 Group. It was full to overflowing, showing the great respect that everyone had for him. Afterwards, many airmen escorted his body to the cemetery where it was interred with full military honours, next to that of Flt.Lieut Day, killed over Balkholme only two months previously. His wish had thus been fulfilled.

Finale

Our daily work continued. The Germans followed our aircraft back to base and once or twice they shot up the airfield but nobody got hurt. Mac, the Signals Clerk had met and married an Australian Flight Lieutenant and left the station to join him down south. Then I heard that I had been posted back to Snaith aerodrome. I was very sad to leave. The office there was semi-underground. I had to leave a lot of friends and return back to living on camp. Life was never quite the same again.

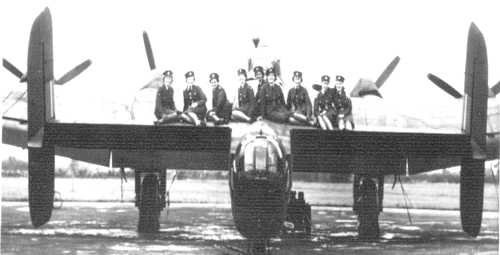

Before we left Burn Airfield the Signals Officer arranged for us to have our photos taken next to a Halifax. It had been a very wet morning and there were large pools of water on the ground. It was suggested that one photo of the WAAF’s should be taken sitting on the aircraft's tail. A ladder was produced and we all climbed up. Some of us were a little afraid of falling off. Then one of the airmen took the ladder away and we were stranded. It was a long drop down into the puddles. They left us there for a while and then some kind person brought the ladder back and we landed safely. It brings back happy memories to look back on the photos of that day and the Peace Parade remembering good old 578 Squadron from 4 Group Bomber Command

(No sting in the tail here! Elsie is fourth from the right)

Peace came at last. We were ordered to attend a meeting in a large building and the news was announced. Cheers and jubilation followed. Victory parades were arranged. The camp was divided into two sections. One attended Snaith church and the other group went to Pontefract. I was in the Snaith party and I remember parading through the small town after the service with children and old people standing on the pavement, all joining in one of the happiest days to remember. One by one we received notice to return back to civvy street. Another stage in our lives had ended – another began.

Rare photographs of 578 Squadron marching smartly through Snaith as part of the Victory parade 1945

Source: Elsie Mackinson (formerly LACW Hope 2135436 WAAF)