|

Norman Davidson: Wireless Mechanic

Many of the airmen and airwomen arriving at RAF Station Burn, in January 1944 didn't know what to expect. Often taking up their first posting from training courses, they formed a nucleus of personnel transferred from the parent 51 Squadron at nearby RAF Snaith. From here a contingent of 131 ground personnel formed an advance party to set up administration of the new 578 Squadron. On the occasion of the move of the advance party from Snaith, it seemed convenient to cover the few miles by bicycle. Those involved were called on parade and ordered to take their speed from a leader. Asked by the Adjutant to give the order to move off, the Station Warrant Officer responded "By the left, quick pedal”.

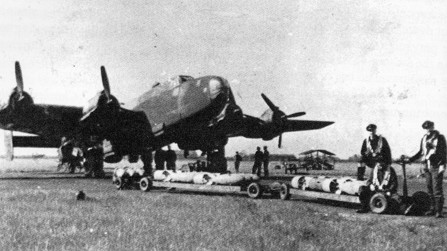

A surprise for many of the new arrivals would be their first sight of Handley Page Halifax Mk III aircraft, 578 being one of the first Bomber Command units to operate this version with its characteristic four radial Bristol Hercules engines.

A good number of new personnel would be of the lowest ranking Aircraftsmen and Aircraftswomen 2nd Class, but all having completed the necessary training in their respective roles, to enable the Squadron to carry out operations.

First duty on arrival, after being directed from the Guardroom would be to report to the Squadron Adjutant's office to be enrolled on the strength. Next to find the allotted living quarters and take possession of one's bed space, literally that in the case of the lower ranks, normally in Nissen huts. Corrugated metal half circular shaped, these came in various sizes, the smallest spanning 16 ft. and 36ft. long. Individual space depended on status with the hut for lowest ranks permitting up to 18 occupants each with 32 sq. ft. sufficient for a bed and room on the floor to leave a locked kitbag. A shelf ran along both sides of the hut for incidentals of uniform etc. In the centre was a coke stove, its chimney protruding through the apex of the curved roof. Accommodation for NCOs and commissioned officers could be in huts with separate rooms and more space per occupant.

New arrivals having reserved their accommodation had then to retrace steps to the main site, living quarters being dispersed some distance from, even outside, the airfield perimeter to obviate risk from enemy bombing. Next task was to complete an Arrivals Chit by reporting to various sections of the Squadron. Essential signatures had to be obtained from Pay Accounts (important to be on the payroll) and Station Sick Quarters. The Station Medical Officer and his staff were not to be routinely on the visiting list of personnel, although a compulsory Free From Infection (FFI) inspection would be an element of the initial contact. Designed to detect evidence of Venereal and other contagious disease, this could be an embarrassing experience. For those who did require medical attention there was a daily sick parade. A most important duty for the SMO and his assistants was to be at Flying Control with the ambulance and crash tender in case of need when aircraft were taking off or landing from operations.

Other important signatures in the arrivals procedure were from the mess appropriate to rank, to be on the ration strength, the cycle store (acquisition of an ‘iron steed’ essential for many to cover the distances involved, the perimeter of the airfield being over three miles).

The next task was to report to the section from which the newcomer would work.. Originally a two flight Squadron, 578 soon comprised Flights A, B, and C, each with eight or more aircraft. Supporting a heavy bomber Squadron, the airfield worked on a 24 hour basis, with a shift system for most personnel, so a community of some 2000 souls soon had the Squadron at an operational peak. In addition to the roles of the seven members forming a Halifax crew, on the ground were numerous duties to perform ranging from the Service Police in the Guardroom, RAF Regiment for airfield protection, Physical Training Instructors Discipline was headed by the Station Warrant Officer, Motor Transport, WAAF Batwomen in the Officer's Mess, padres, gas and fire sections as well as catering, sick quarters and pay accounts already mentioned, all played their part. Buildings on the Admin and Technical sites were bases for departments ranging from the Control Tower, Fire Section, the various dining halls, NAAFI canteen, gunnery and bombing trainers, fuel stores, gymnasium and telephone exchange.

On The Job

The airfield itself was necessarily an open space to permit aircraft landing and taking off from the three intersecting runways, according to wind direction. The aircraft numbering some 30, again to reduce the risk from enemy attack, were dispersed on ‘frying pan’ shaped parking places around the perimeter track. ‘A’ Flight began at the Southern end of the site then clockwise through to ‘B & C’ Flights. From here the various trades involved with aircraft maintenance would carry out their duties. Permanent buildings on the airfield proper, were limited to the Control Tower and hutted Flight Offices. Headed by a Flight Sergeant each Flight would have sufficient engine and airframe mechanics, (fitters and riggers ) who, working in teams would be responsible for maintenance of their ‘own’ aircraft. In view of inclement weather primitive shelters would appear on each dispersal.

Other personnel working on the aircraft were termed ‘gash trades’ by the fitters and riggers. These included electricians, instrument mechanics, wireless & radar mechanics, compass adjusters, safety equipment assistants and camera installers. Most of these personnel would work from their own sections on the technical site, but be available to service any of the Halifax’s on the three Flights. Armourers (bombs and guns) hail from the armoury or bomb dump site which was to the North of the airfield.

The various technicians servicing their equipment tended to drain the aircraft's internal batteries. It was preferred that an outside source of power was used by plugging in a ‘trolley acc’ which held heavy high capacity batteries and was also the means of starting the four Hercules engines of the Halifax, which drew an even heavier current. Accordingly the trolley could have on top, a ‘chore horse’ petrol electric set to recharge its own batteries.

Whilst work on the aircraft was going on, a welcome sight for air and ground crew alike would be the frequent arrival of the Salvation Army (Sally Ann) mobile canteen.

Following a cry from the first airman to spot its approach, bodies would tumble out of aircraft to form a queue for welcome refreshment.

Serviceability of each aircraft depended on its Form 700. Held in the Flight Office, malfunctions (snags) being reported after flights by aircrew or found by ground crew on routine inspections were recorded. Theoretically a pilot would only accept his aircraft after all the repairs had been carried out and signatures of ground crew obtained. Fitters and Riggers particularly would only ‘loan’ their aircraft to its aircrew with the plea, "Bring it back in one piece".

It is perhaps no coincidence that given the comparatively short life of the Squadron, three out of the four Halifax bombers known to have completed at least 100 operations, served with 578 . Their serial numbers and identity letters LV937 X & R which completed its century after being returned to 51 Squadron at Snaith, LW587 V & A and MZ527 W & D. The latter two completed one hundred operations on the same night raid to Kamen on 3/4 March 1945.

Aircraft were subjected to between flight inspections and also daily Inspection by the various ground crew. After intervals of 50 flying hours, in-depth servicing was carried out, normally in the hangars or at the parent unit Snaith. During the life of a Squadron, advances found necessary in the course of operations involved the installation of additional or improved equipment. The necessary modifications could be carried out on the Squadron, or some distant Maintenance Unit or aircraft factory.

It wasn't always that problems arose from operational or training flights. On 27 May 1944, with 23 Halifax’s prepared for a night operation to a military camp at Bourg Leopold near Brussels, a crew arriving at their aircraft found a swarm of bees had invaded the space between the port fin and rudder of, perhaps appropriately Q -Queen. A local beekeeper was called and eventually Queenie took off as planned. On return, Burn was closed because of fog and all aircraft were diverted to other airfields. Next morning, when Q returned from Silverstone and as its engines were shut down, ground crew observed a bee hovering by the tail fin - perhaps the only one of the species to complete a bombing raid.

Busiest time at Burn would be when it was announced that "ops are on". In advance of the takeoff aircrew would assemble in the security of the briefing room, informed of the target, the bomb load, route, take off times, weather conditions predicted by Meteorological staff, and intelligence on likely enemy defences.

Before collecting flying gear and parachutes there would be a traditional meal, probably bacon and eggs, then with flying rations crews being taken to their aircraft in crew buses or lorries, often driven by WAAFs. The Motor Transport section would also have been involved with petrol tankers refuelling the Halifax’s, and tractors bringing trains of bomb trollies from the bomb dump. Armourers may have been required to change the bombs already loaded on the aircraft. Similarly riggers fitting long range fuel tanks when, as sometimes happened, the target or aims of the raid were changed at the eleventh hour. Tradesmen would make final adjustments to their equipment on the aircraft. Unless, at the last minute the operation was ‘scrubbed’ - ops would really be on.

Then the anxious wait for the return of the Squadron's aircraft, hopefully intact. It wasn't all over until the Halifax’s were bedded down, the various ground trades helping each other putting covers on wheels and still hot engines, and ready to act on damage repairs and other snags. Aircrew meantime to be debriefed on all aspects of the operation by Intelligence Officers. With the Squadron Operations Record Book

and aircrew log books completed, another of the 30 operations of a tour would be completed.

On the occasion of one operation, the Commanding Officer, Wing Commander Wilkerson ended the pre take-off briefing with the admonission, "I'm to be first home tonight." Enough said, one returning aircraft dutifully held off landing to permit the CO to be first home. This, in his quiet way, was to enable him to emphasise the Squadron's bombing accuracy to an assembled press corps. He used the expression, ‘The Aiming Point Squadron’, which caught on with the journalists, subsequently giving rise to the Squadron's motto ‘Accuracy’. This was duly incorporated in the 578 badge approved by the King when the unit disbanded in 1945. Depicting an arrow split by another, the design was based on an ancient Greek archery competition when the last but one arrow hit the bull, only to be split in two by the final competitor.

After each operation the exposed film from aircraft cameras was taken to the Photography section, developed and printed. Examined to assess the success of the raid by each crew, the prints were eventually displayed for all ranks to see ’Accuracy’ for themselves.

Red letter days for the junior ranks were the fortnightly pay parades. Held usually in a hangar or other suitable space, a WAAF pay clerk would read out names alphabetically, and the amount payable. Each airman stepped forward to the paying officer saying, "Sir" and the last three figures of his service number before saluting and marching away to check the amount received. (He would remember his complete service number for the rest of his life). Normal fortnightly pay for an Aircraftsman 2nd Class was at the rate of 3 shillings (15p) per day, drawing 2 Guineas (£2.2 shillings) every other Thursday. With tradesman's pay and promotion, the amount rose accordingly.

Off Duty

It did not have to be all work and no play, with off duty personnel, with perhaps an all ranks dance in the Airmen's Mess, an ENSA show in the camp theatre or just a cup of char and wads (tea and rock buns ) in the NAAFI keeping many occupied on site

During the fourteen month occupation of the airfield, Squadron personnel enjoyed good relations with the local population still evidenced today by inclusion of the word Burn in the 578 Association title. Local farmers and villagers invited off duty staff into their homes, with in return assistance being given by airmen to help at harvest time.

An amusing incident can be recalled when an airman, finding the village post office in the front room of a house on the main street, asked for a one pound Postal Order. “Oh, I've sold it" said the postmistress - a sign of wartime shortage no doubt.

In and near the village were a number of watering holes, closest being The Wheatsheaf, and down the road by the bridge over the canal, the Anchor Inn. The Methodist chapel was a peaceful haven for some. Further away, it was three miles to Selby, with more watering holes, the Londesborough Hotel with the splendid Abbey forming an imposing backdrop. This Inn was regarded as a bit of an up market venue, mainly frequented by aircrew NCOs and officers.

Church Hall dances and cinema were other attractions Then it was back to camp by bicycle or the Liberty Bus transport sometimes available.. Other more distant off duty locations were Knottingley, Pontefract and York with its famous Bettys bar and restaurant.

Between periods of frenetic activity life on the Flights could on rare occasions leave time for other interests. It wasn't long before ground crew at their dispersal shelters began to accumulate a collection of pets. Some of the aircrew had dogs, kept on living sites but on ‘A’ Flight, C-Charlie’s dispersal, a lone duckling was joined by more of the breed, obtained at a local market. In no time a special area was provided for 26 ducks, some drakes and a goose. Even a small pond was enlarged, and eggs were soon being enjoyed, cooked on a makeshift stove. Other dispersals had a goat, a cockerel and a ferret, the latter in demand for catching rabbits, a welcome food source for airmen to take home on leave'

Crew and supernumeraries on their way to aircraft, and disembarking after successful sortie

Conclusion

578 Squadron was a proud unit to have served with, the job done through thick and thin with a minimum of ceremonial parades largely thanks to direction from the top by Wing Commander Wilkerson, our highly respected first Commanding Officer. He engendered the will to succeed by his example and encouragement to all ranks and could be approached directly by anyone with a problem and do his best to solve it.

Airframe fitter Corporal Ted Bland, explained how this was achieved.

Our Squadron had the finest C O in the Royal Air Force, Wing Commander David Wilkerson DSO DFC, known as 'Wilkie' to us all. He was one of England's gentlemen, extremely kind and fair to everyone, no airs or graces, and concerned for the welfare of aircrew and ground staff alike. He had the very rare trait of being a good listener, which was a marvellous asset in a leader of men, so much so that shortly after the Squadron was formed, he set up a Welfare Committee to hear moans and groans and to receive suggestions. I was privileged to be a member. I recall being summoned to his office when he asked me, "Are you the NCO who wrote to Captain F J Bellinger MP and John Bull Weekly whilst at Snaith in 'C Flight?" I replied, "Yes Sir." He asked me what the complaint was about and had the grievance been rectified? I told him that it had. "Do you regret your action?" he said.

"No Sir."

"Have you suffered in any way?"

"Not really", I replied ,”other than I was sent on a strict disciplinary course for 21 days at Cosford under Flight Sergeant Chang (known as Orang Utang the b------d,) which made me very fit."

'Wilkie' then asked me if I would serve on his proposed Welfare Committee each Wednesday morning at 10.30 hours and represent the ground crew. I was proud to do so. This, surely, was a man above all others!

It was due to this strength of spirit and respect, engendered during our days at Burn, that veterans lost no time in founding the 578 Squadron Burn Association after the Squadron was stood down in 1945. That same spirit has ensured its continued existence ever since.

source: ‘Norman Davidson’ and Based at Burn MkII