|

Norman MacQueen (Wop) Holds Forth.

I joined a bank at sixteen and got the princely sum of three pounds a fortnight from the age of seventeen. I tried to do a pilots course but was told that as there was a war on I would have to join the Air Force which I did at eighteen and was called up a few weeks later.

A couple of things stand out at the I T S. We had a big bull of a Sergeant Major - not very tall but with an enormous top to his body, arms so big that they hung about one foot out from his waist. He used to yell at us all the time, fitting in as many swear words as he could. However one beautiful day an order came out that all ranks had to wear shorts. Now this was Brisbane Queensland and all of us LAC's came from up that way, lived in shorts and our legs were all black. Well the next morning on parade and with all the officers lined up in front of us with these lily white legs, the poor old Sergeant Major sporting the thinnest white legs we had ever seen. We behaved ourselves for a couple of minutes then we all roared laughing. The poor old Sergeant Major started to dance up and down, waving his arms about, which of course made it worse. Poor bloke I forget what happened .

The next thing of note was all our injection shots. We were in single file and a bloke each side jabbed a needle into both arms and after squirting the contents disconnected the syringe part leaving the needles in place for the next couple of clowns who connected new syringes to them and pushed the plunger before removing the lot. Further up the line we were jabbed with something resembling a small porcupine before being helped to a door, down a slope onto a lawn. Where, funnily, it seemed to be the biggest bloke who flaked out.

About a week after this the powers that be decided to have a march through the city of Brisbane by all the services and we were picked to represent the RAAF. Apparently, even after that time the injection shots had a such a bad effect on some people that they collapsed. Our section of the parade ended up with a vehicle following on behind and picking up all the flaked out bods. Must have been a good advertisement for the public!

I was classified as pilot material and posted to a local training school using Tiger Moths. I was given an instructor and off we went. No trouble with takeoffs, straight and level, turns, spins, forced landings and even ordinary landings so off we went to do a bit of low flying. This I really loved, but I did feel a bit sorry for the poor old cattle and sheep. After about eight hours I had lost the knack of landing, after about ten, with no solo, it was a case of waiting for the scrub machine.

I was a very young 18 and my life's ambitions started to fade. The chief flying instructor kept me waiting for two days, anyway off we went. Everything went perfectly ‘till the landing. I actually did a nice touchdown. Ahead was another aircraft. It was an all over grass paddock and as this nit was taking off at about a 45 degree angle to us neither my instructor or myself noticed him, but when I did I opened the throttle and flew over the top of him, doing a good touchdown the other side of him. I taxied to the parking area feeling very pleased with myself, turned off the engine, and then saw the look on my examiners face. Back to ITS and although I'd got 85% for navigation and only 52% for wireless I was put down as a future WOP which was what were needed at that time. My air force career would have been very brief if I'd got my wings as all those poor blokes wound up in Darwin against Zero's, including a good friend of mine.

My next step was to a holding base near Sydney I was very lucky here for as no one seemed to have any decent photos or models of Jap aircraft volunteers were called to make small models. Three of us ended up in this job which was very interesting. All we had were some very poor photos and drawings to work from. We would concentrate on one aircraft and all make our own sketches as to what it really looked like. One of the drawings would be selected from which we would make the models which could not have been too bad as they hung in a room on the Squadron for a long time. So our day consisted of morning parade after which we were dismissed leaving the rest of the day ours to do our job.

Unfortunately the day we finished the model work, two of my relations from Fiji were on holiday in Sydney. Obtaining a leave pass for the night, I went to see them I had never drunk much alcohol before - my usual drink when I went a pub was a sarsaparilla or, if I felt extra brave, a double sars , but this night I had a few wines, and even next morning I still felt a bit woozy.

Back at the camp that day it was decided to have a route march (the bush was very thick adjoining the camp). and after a couple of hours we came to a beautiful little stream, at which I drank and drank, and, blow me down, I was full again. I was assisted back to camp where I had a lot of trouble convincing the powers to be that I had not been drinking that morning. I was put on guard duty in front of the officers mess. Well, just slapping the butt of the rifle was OK for most ranks but then up comes the CO. Well I mucked about a bit for a while trying to get the salute right but in the end I said "Sorry sir I can't get it right but this is how it ends." After tea that night, I was out onto the middle of the parade ground practicing the salute. You can imagine all the advice got!

Next day we went down to the wharves in the middle of Sydney Harbour and boarded this beautiful looking single class vessel of about 18000 tons. We were shown to our cabins, equipped with two beds. The only other passengers were wives and children of Dutch diplomats from the Islands. What a way to go to war!. Our protection on board were a couple of machine gun nests, and a 3 inch gun on a small deck on the stern of the boat, machine guns worked O K, now for the cannon, it fired alright but, split the deck, so it wasn't tested again.

Leaving Sydney we travelled due South for many days, and it got really cold, we then headed East and then North again to arrive at Wellington New Zealand)and. I had never seen such green, I had lived in Maryborough Newcastle and Brisbane and the green grass was fascinating. Blow me down , I was on gun duty for about half the time everyone else was ashore, but I did see the place for a couple of hours. South again and cold, East and North. We ended up in San Francisco,passed under the Golden Gate bridge and we were there.

Into a train that night and a couple of days later got in Winnipeg, the trip was very interesting, but everything was white, and flat in all directions, this was after the Rockies of course, but we had travelled over that at night.

The Wireless school we were bussed to was an old deaf and dumb asylum. The course took about eight months and covered many subjects the hardest of which was meteorology, why that for a wireless course I have no idea. Our main subject of course was Morse Code in which we all had to get up to 20 words per minute (a word consisting of five letters or figures) that is one and three-quarter letters or figures we had to be able to send or receive and write down per second, most of us got to 25 words per minute., it was a funny thing to learn, as it just had to come to you without thinking, if ever you had to think what letter it was ,you had had it.

Canada at that time had very strict alcohol laws for example no one could buy any other alcohol, except beer until you were 21,or go into a pub bar ,except if you we in the services, so the sly grog blokes did well. I meet one on a street corner in Winnipeg who told me he had very good rye whisky. I stupidly bought a bottle and a friend and I took a couple of swigs, my swig must have been a lot bigger, as my throat burnt so much I thought I'd kick the bucket. I was in hospital for about a week and told I'd be on a charge, I could only eat ice cream for about four days and was told I was indeed very lucky it had not done any permanent damage. I was not charged.

Wireless operators from civilian life, mainly from fishing boats were trained to be officers at our camp, we called them the 6 or 12 week wonders. During our training in Canada, things were not going very well back here with the Jap's getting closer and closer, we made many attempts to get back to Australia, but of course we couldn't, about three very ignorant people back home actually sent white feathers, one of my friends was very upset with this, considering it was his so called girlfriend, the Australian Ambassador from Ottawa came to visit us, mainly about this matter, pointing out that we would be a lot more valuable as trained servicemen also the names and addresses were collected of those who sent the feathers, my friend unfortunately did not get over the letter. I don't know what happened to him.

Our next move was to a gunnery school as we were to qualify as wireless air gunners. This was held at Moose Jaw, just west of the Rockies, terribly cold. One day they had heaters going in the hangar to warm up the engines a bit and melt the oil. I was in the next lot to fly and was getting ready when it landed early, an ambulance charged out and a poor bloke before me was carried out, his whole face dead white and the size of a balloon, the combination of less than 40 degrees below and the wind coming into the turret at probably at least 1OOmph did not do much for any part of his face unprotected, flying was cancelled for the day. I was then posted to Sidney on Vancouver Island for a torpedo bomber course before returning to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to await a ship to take us to England.

Our trip to England was considerably different than the one to Canada. I just can't remember the name of the vessel, The Himalaya I think, but I am pretty sure that it was the third biggest in the world, conditions were terrible, the powers that be even apologised for the terrific numbers on board The room the Australian air crew had ,was quite big ,with a few tables arrangements for sleeping on. There were beds on the floor, some on the tables and hammocks, I grabbed a hammock, lot better for sleeping on a boat, but the air up there was putrid.

At one end of the large room there were stairs leading down to another room, this was crowded in the same way, but oh boy, the blokes in their were all graduated sailors ,but had done all there training on the great lakes, many had never even seen the sea, and they were a real mess most of them were sick, all with their buckets, which had to be emptied by them into the sea, which meant coming up the ladder and through some of our area to the door to the deck, this door was open during the day but unfortunately, shut at night and no one and I mean no one was allowed on deck after dark, there were also quite a few very sick in our room It was some trip. I was OK but did not eat any of the meals, the food was terrible, we the other ranks, did not have a shop but the officers did so organised choc ,sweets and cordial for myself from an officer friend.

On the whole trip the boat went flat out, we were not in a convoy every now and again turned so sharply that it tilted, there was one very good thing and that was it was very rough all the way which made us safer from sub attacks, what a target we must have been, thousands of trained troops, I use to spend all day, everyday on deck mostly out front just below the bridge, this deck area was unprotected, so I use to hold onto railing very hard and watch the bow of this huge vessel plough under the giant waves into dark green water ,and through it back over itself as it came up, I knew I would never see such a sight again in my life. In peace time a beautiful ship like this would never be pushed like this in such conditions, it vibrated and tossed about the whole time. I would stop on deck until I either got too cold or my overcoat too wet when I went down into our unit, put my coat over a heater where it steamed and soon as it got nice and warm, on with it again and up to the bow, believe or not I was the only one there.

Just before we arrived we went through the middle of a convoy, it was as if they were standing still, of course they could only go the same speed as the slowest vessel and there were sure some old rust buckets amongst them. One thing I did see, were Corvettes. They were very small and I would just see them now and again for a second. I had good friend after the war who served in them he ended up with what was considered a corvette disease, which was TB. He said he was wet all the time even in his bed which he shared with someone on the next watch, but he did say it was at least nice and warm.

We docked in Portsmouth in the dark just during or after a raid, we were warned to get ready to disembark, still fires everywhere, we were got off and immediately bussed to Brighton, this was a holding place for mainly Air Crew. Australian other ranks ,and the officers were in a separate hotel about another block away also on the foreshore, we were in the Metropol which became famous many years after the war ,when the British Conservative Party were holding their Annual conference with Mrs Thatcher as Prime Minister and someone tried to blow up the place. I was bored stiff in Brighton which was also very cold. The next stop for training was Wigtown in Kirkcudbrightshire and then Lossiemouth, all equally cold.

578 SQUADRON

We carried a bit of practice with local flying when we first got to 578 and on one of these exercises I reported to the skip that our generator had broken down and advised that I had no idea how long the wireless or intercom would last. J didn't like the idea of flying around England, in the dark with no communications, so he decided to land somewhere. We were over a strip so the skip asked details from the navigator who reported the length of the runway, which was pretty short. As we flew over we saw a Liberator just off the end of the strip, so the skip said "If a Liberator can land there ,so can we" and we did so quite successfully, but when we got down we found that the Liberator had run off the end of the runway and was stuck in the mud.

We carried a bit of practice with local flying when we first got to 578 and on one of these exercises I reported to the skip that our generator had broken down and advised that I had no idea how long the wireless or intercom would last. J didn't like the idea of flying around England, in the dark with no communications, so he decided to land somewhere. We were over a strip so the skip asked details from the navigator who reported the length of the runway, which was pretty short. As we flew over we saw a Liberator just off the end of the strip, so the skip said "If a Liberator can land there ,so can we" and we did so quite successfully, but when we got down we found that the Liberator had run off the end of the runway and was stuck in the mud.

We had a great night, the aircraft we were in had done quite a few ops and there were bomb drawings on the nose showing it had, we were treated like heroes, no need to point out that the trips were not ours, and we hadn't even started them yet. The ground staff fixed the generator over night and we got back at Burn next morning.

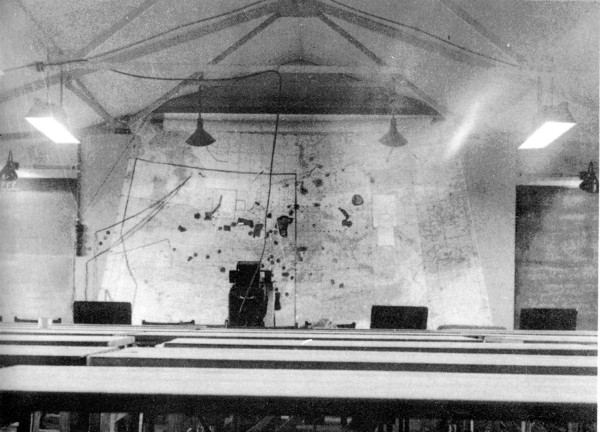

The notification of an op. and those to be on it, first appears on a notice board and as soon as this happens, all movement both into and out of the airfield ceases. The crews to be involved would be seated then, right on time arrived the CO, chief Intelligence Officer, Met Officer, and anyone else needed for the briefing. A large map of Europe is then pulled down or uncovered, and on it was pinned a zig zag tap to the target. The met bloke gave us the expected weather. Our Navigator got a more through briefing after the Intelligence officer gave us details of the target, turning points, main flack areas, supposed proximity of the night fighters. Then after best wishes from the CO. we all went to our own sections to get further briefings, plus the codes for the day before meeting up with the crew again to collect parachutes etc.

The 578 Squadron Briefing room at Burn

All the crew wore battle dress which consisted of the usual uniform with blue shirt and black tie, but instead of a coat we wore a jacket and wool lined boots. My shoe size was 9 and the boots size 12 with the top stitched on to the bottom, so if we were shot down we could cut the tops off, with a little knife in the boots, when they then just looked like oversize shoes. We all had at least two compasses hidden on ourselves, and two fly buttons which could be cut off, one of them having a small point which pivoted on the other and a magnetised head with a small dot showing magnetic north. I also had a pipe with a compass hidden in the mouthpiece (wish I still had it).

We had electric vests to plug in, wool lined gloves, a beautiful soft leather helmet with ear pieces and mike, silk maps of Germany, army rations, and revolver. We all learned a few essential words of German like good morning, and good night to be pronounced in different ways for north and south Germany. We had all the daily codes on rice paper and a thermos of black coffee. The ground temperature in winter was generally freezing or below, and as the temp drops by 2 degrees every 1000 ft of height it was pretty cold at about 20,000 feet, when pouring our hot drink if a bit dropped on the rice paper, it did not matter as it was ice by the time it hit, so it just brushed off. We also had a bit of survival training what we could eat etc, also commando training, how to sneak up to someone and garrotte them, and other nice things like that.

The first op. we completed I remember very well. It was a beautiful Autumn day cold but very clear and the target was the Krupps Steel works in the Ruhr, the industrial heart of Germany and very vigorously protected. After leaving England, aircraft from the different Groups met at a planned area over the British Channel, to form a Bomber Stream. The first part of the trip was beautiful, flying over France all the fields spread out below and as far as we could see each side of us were aircraft.

There was a Lancaster quite near us at the same height, and once it drifted right over beside us and we all waved and gave the thumbs up, he then drifted away, I was standing on the starboard side watching when suddenly there was a big flash and the Lanc disappeared from my sight. Our gunners watched what was left of it fall to the ground, but no sign of a 'chute. I held on like billyo as our aircraft was well and truly bounced about and then sat down very quietly, realising, that I was really in the war.

The track to the target was carefully planned to miss any fortifications so we did not get much flack, but, of course, as we got in deeper it increased, just blacks puffs in the sky, generally a group of them at the one level, I think it was six at a time (I certainly remembered then) and we automatically counted them as they got closer, and breathed a bit of a sigh when the count finished, especially if they were getting close for after that number they had to put another rack of shells in. Where the flack was thick we use to drop window, another of my jobs, which consisted of rolls of aluminium strip about 12ins long held with rubber bands ,they varied from about inch to 3 to 4ins wide, and about up to l yard long. There were quite a few in each bundle and I dropped them out through a little slit in the fuse box.

Now as I've said, Radar was very primitive at that time mainly blips, different size window, gave the same blip as an aircraft on a certain frequency and with 200 or more aircraft dropping them it we got a pretty good cover. Because the Germans were starting to line their guns with radar and at night, searchlights and radar, any poor aircraft that got out of the bomber stream in bad areas was a sitting duck I have seen on many nights aircraft coned with search lights, and if they couldn't get out quickly, end as a big flash. We were coned a few times and the skip turned that aircraft inside out.

As we got near our target the skip said ,"At least we know we are on track". I looked ahead, and in the sky was a giant black dot, the Germans as I pointed out did not have much of a chance of hitting us in a bomber stream, but near a target all the aircraft converged into a narrow track lining up the flares, so what they did was to have hundreds of guns around important targets and concentrated them on one small area in the sky. They knew for example that our bombing heights would between 18,000 and about 28000 feet so they just filled this area up with flack as fast as they could fire. It was quite weird flying into it.

As I said this day was bright and sunny but inside the patch it got pitch black then flashes of both sun and explosions when the aircraft would bounce about and hopefully only small pieces of shells hitting us. At night of course you could leave out the flashes of sunlight and we would have tuned to the pathfinders by now and the bomb aimer, who had taken up his position over his sight, was being directed by the Master Bomber as to which flare to bomb, so the bomb aimer would be calling left, left steady right steady, then bombs gone (this was very unnecessary as the aircraft would leap up into the air). The skip would wait for a second or so for the camera to work, then down into a turning dive to get out of there as fast as possible.

After diving away from the target area the gunners kept a special look out for fighters, as we were on our own now. We always had our fingers crossed returning as there were many reasons to divert us elsewhere, the most common was fog, then I suppose enemy aircraft about. It was unfortunately not uncommon to be shot down when landing back at base, the aircraft slowed right down and I suppose a certain relaxation on all our parts. Another reason for being diverted was if one of our aircraft had pranged on the runway.

A pilot was always careful after his aircraft had been hit to make sure there was no bad damage, and if there was to land on one of our crash sites, I think there were about three ,the one we used was Manston. This runway was probably a couple of miles long and very wide equipped with fire engines, heavy moving equipment and ambulances with staff dotted all along it.

On arriving back to base, or anywhere really, we were debriefed, here we were given mugs of war time coffee, but with plenty of rum in it. When it was our turn the whole crew sat at a table with an intelligence officer, answered any questions, and, giving our own observations, for example any aircraft we saw shot down, exactly where, whether we saw any chutes, a couple of times in daylight hours one of the gunners saw VI or V2 taking off (these places would immediately be attacked), types of fighters spotted ,etc., We then retired to our own department briefings if necessary, and then to the mess and bacon and eggs, a real treat for war torn England, then bed, and possibly, another op that night.

When the weather was not suitable we got a few days off and even a week sometimes. Most of these times I would go to the Kipling Coats farm, after a while I was even given my own bedroom and bed, and I will always remember this bed, some nights even after an op, if I knew there was no flying the next day, I would get on my old faithful BSA bike and ride to the farm, where I would sneak up to my room and get into bed, out the window there used to be a big Barn Owl only a few yards from me, under the top corner of the barn roof. Once I was in bed with a mattress filled with down and before I had finished sinking into it I was asleep. The first the Clarkson's knew of my being there, was when I arrived down for breakfast. I loved it there, war seemed miles away, I use to make myself useful around the farm, or I think I did!

Back to flying. We were attacked by fighters at least three times and thank goodness the gunners spotted them before they got close enough to fire (about 600yds) A bomber hasn't got much chance if a fighter is not spotted early as practically the whole of our wings contained fuel, or even empty fuel tanks. If seen early enough the bomber can generally out manoeuvre the much faster fighter. A tropical encounter would be our mid upper calling "Suspicious aircraft 20 to 12 skip, then, it's a JU 88 prepare to corkscrew to port, then 800, 750, 700, 650 go". With this the plane would turn onto the port wing and into a dive, turning to starboard as it went down, then a sharp climb, quite a sensation especially with a fully loaded aircraft. They were certainly built strongly. One of our blokes was repeatedly attacked by a fighter on the way home and still managed to survive.

During the last few months of the war all of us had air to ground radar, this allowed the navigator to recognise different areas, depending on the direction he approached, if for example this was from the Ruhr from the north, he would be given a photo of that area that had been taken previously by a Mosquito on his radar which was a great help. Water showed up very clearly on the screen. I, as wireless operator had a screen, and this showed a small area around and below the aircraft, I could see dashes following us on the same course.

On one trip, one fighter came in on a slight angle and then changed course to follow us. I got the skip to turn slightly to port and so did the dash. We straightened up again and so did our shadow, which was catching up rapidly. When it got to about 650 yds I instructed for a corkscrew and we lost it.

For a few months at one stage we started to lose many aircraft to fighters, and none of them had been spotted. It was found out eventually that the Germans had mounted an angled up cannon in some of the fighters, which allowed them to approach unobserved by either gunner and then fire up into the aircraft from below. I read a report not long ago from one of their ex fighter pilots stating that they purposely fired for the wings, to give the crew a chance to get out. What a load of rubbish, the wings were the obvious place for if they concentrated on the fuselage they would probably get some of the crew but not necessarily shoot the aircraft down.

On one trip to the Ruhr we were hit in the outer starboard engine when the bomb aimer was up front and we had commenced the bombing run. The aircraft suddenly jolted violently, just about turned over. I was out of my seat grabbing for my chute, when the voice of the bomb aimer came over the air "how the hell do you expect me to bomb when you can't hold the xxx aircraft steady?" I very sheepish and sat down again. The trouble is that we all knew that if we once got into, what we called a death dive, there was very little chance of getting out, the centrifugal forces being so great that even to move is impossible. Our skip got it level again, the bombs were dropped, and when the bomb aimer passed me,I realised he didn't even have his chute on. He inspected the plane and reported quite a bit of damage, so off we went to Manston.

Before landing the skip told us all to get into our crash positions, which for most of us was lying on the floor about midships, between spars and hold on tight. He put the Halifax down very gently but, on landing, there was a terrible screaming sound as our poor old plane disintegrated. From my position I could see the bomb aimer on his folded seat beside the skip when he suddenly popped up in the air as the sides of the aircraft came in and buckled his seat.

The row eventually stopped and we were all lying a little dazed I suppose. Men appeared and pushed and carried us out of the wreck. A bull dozer then arrived and pushed the poor old remains off the runway. After a while a truck came to pick us up, then the usual exercise, coffee and rum, debriefing and our fried eggs and bacon. We were then shown into a big room with double decker beds everywhere, officers and other ranks all mixed up.

We met a Lancaster crew all as white as ghosts and unable to stop talking. They had been on the same op as us and also had been hit over the target, got into a dive and were all stuck to their seats When they eventually pulled out they could see people running in the street. Our skip went and saw an orderly, suggesting they should be hospitalised for the night and they were taken away.

Terrible place to be, it had been a bad raid and all night long there were flashes and explosions Next morning there were wrecks of aircraft practically the whole length of the long runway. We had to take all our stuff, including, what we could salvage, right through London, where we were treated like heroes and showered with drinks where ever we went.

We had the next night off ,but up again the night after and, blow me down, we were attacked by a JU88 near the target I don't think it was the fighter, but that was the time our mid-upper turret was put out of action. I don't know what would happen these days, when they send councillors to warships when one of their aircraft crashes. On an RAF base there would be more councillors than flyers. In our day if a pilot crashed even in training, he would be sent up again straight away.

Hallifaxes (or Hallibags as we called them) unfortunately had a tendency to coring, this being the blockage of some oil pipes in the engine. Unfortunately we had to abort at least three ops. for this reason.. A tour was only counted in the magic figure of 30 un-aborted opps, which at times was very unfair. For example, once we had gone quite a long way, when we lost one engine (that is, it had to be shut off) then another when we were still over France. We did not want to drop our bombs there, so over the English Channel we had to circle for a while to get a break in the clouds to make sure we didn't bomb a convoy or anything else. The skipper as usual brought the aircraft down quite safely. He was popular with all the crew and obviously very good at flying.

All Australian air crew were grounded after VE Day and shortly after I was called to the office and given orders to another squadron, so I could not even say goodbye to my crew. I gave my bike to the ground staff, I also had a very good wireless set but, I can't remember what happened to that. The station I was sent to had all Australians waiting to get home and a lot of crews from operational Squadrons arrived over the next few days.

We left from Portsmouth I think and we certainly got a send off from the both the Navy and the Air force. Dozens of different types of aircraft really buzzed us. Quite a good trip home. The ship was a floating gambling den, and we had piped music, the popular stuff as well as a chap explaining classical and playing it.

We were a long way from shore off WA but one morning we were all on deck smelling eucalyptus, but we never did see the land until we arrived at Melbourne, but the smell was beautiful. On the ship many people asked me what Tasmania was like, as that was the written on my kit bag. I had to admit I had not a clue as I had never been there. My sister Pat met me somewhere, I think it was Launceston, and we entrained to Hobart.

Well that's about it, all seems very strange to me now, it was so much different to the present day that I thought I would write it all down before I forgot everything, or kicked the bucket.

source: ‘Norman MacQeen ' Wireless Operator